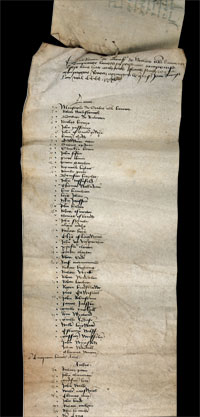

Muster Roll of Lord Thomas Scales' Company

NAM 2002-07-164-1

A new type of Army

This roll, written in medieval French, lists some of the ordinary men who served in English armies of the Hundred Years War (1337-1453). In total, Scales supplied some 728 archers and about 50 men at arms for the Siege of St Denis in France. Scales’ men were armed with longbows and early firearms. The development and adoption of these weapons meant that the nobility was no longer the deciding factor in battle. Peasants armed with longbows or firearms could attain the power, rewards and prestige once reserved for knights. The composition of armies changed, from feudal lords who did not always respond when summoned by their lord, to paid mercenaries. Scales’ men for example, fought under a contract for regular wages. During the war, English kings were able to raise enough money through taxation to create a standing army, an entirely new form of power for monarchs. Not only could they defend their kingdoms from invaders, but standing armies could also protect the King from internal threats and also keep the population in check. It was a major step in the development towards new monarchies and nation states.

Tudor cannon

NAM 1991-11-41

Smashing stones and bones

The barrel of this 16 foot long bronze saker cannon, manufactured in London around 1530, is inscribed with a Tudor rose and a monogram of King Henry VIII. In the 16th century cannon were given the names of birds; a ‘saker’ was a type of hawk. The saker fired solid iron shot, weighing between 1.8 and 2.7 kg (4-6lb). These would not explode on impact, but would bounce along the ground until they crashed into something – or someone. Cannon balls could smash through stone, brick, flesh and bone with ease, but might be stopped by gabions, defensive baskets filled with earth.

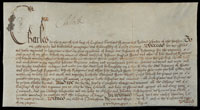

Warrant authorising Lord Willoughby of Eresby to raise the regiment that became the King’s Lifeguard, 1642

NAM 1993-10-112

A Royal challenge to Parliament?

King Charles I signed this warrant at Nottingham in August 1642 on the outbreak of the English Civil War (1642-1651). The King was raising an army using the ancient system of a Commission of Array, whereby he granted a commission to an officer in a specific area to muster the local people. Out of date by the mid 17th century, the process was revived by the King in direct opposition to the 1641 Militia Ordinance that had given Parliament control of raising troops. By issuing the warrant, Charles was raising the fundamental question: who controlled the Army? Crown or Parliament?

Pikeman’s armour

NAM 1996-07-279

Pots and plates

This armour consists of a pot helmet, back and breast plates, tassets to protect the lower trunk and thighs and a gorget to guard the throat. Dated from around 1640, it would have been worn by a pikeman. Although around two-thirds of a 17th century infantry regiment would have been armed with a matchlock musket, the rest of the troops, many of whom continued to wear armour, would have used a sixteen-foot, steel-tipped pike. A pikeman’s armour could weigh between forty-five and sixty-five pounds. One of their key roles was protecting musketeers from enemy infantry and cavalry. When grouped closely together with pikes held out, the pikemen could hold off an attack by enemy horse.

General George Monk, 1st Duke of Albermarle

NAM 1985-02-1

The most powerful man in England

George Monk (1608-1670) is one of the enigmas of the English Civil War (1642-1651) period. After serving with the Dutch in the 1630s, Monk fought for King Charles I in Ireland and England before his capture by the Parliamentarians at the Battle of Nantwich in 1644. He then became one of Oliver Cromwell's most effective generals and his deputy in Scotland. Though courted by the King in exile, he remained loyal to Cromwell, publicly proclaiming his support for his son Richard on his accession as Protector in 1658. It was only in the face of political chaos that he secretly responded to approaches from Royalist leaders. In the next months he applied himself to the delicate task of reconciling the republican army to growing public sympathy for a restoration of the Stuart monarchy. Marching the Army south from his camp at Coldstream on 1 January 1660, he became the most powerful man in England, securing the return of Parliamentary government alongside the restoration of the Stewart monarchy. Monk was thus an effective diplomat as well as an able soldier.