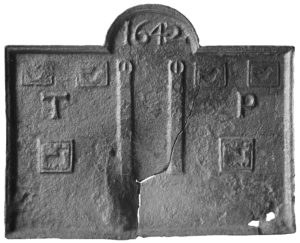

Most armorial firebacks commemorate the reigning kings and queens, or the major families in counties, regions or the country as a whole, as well as several that show the arms of London livery companies, so it is somewhat uncommon for two very different firebacks to bear the same arms of a married couple whose milieu was confined to provincial society in eastern Sussex.

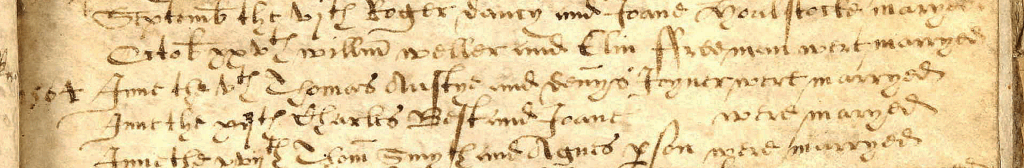

Thus was the case with George Worge (1705-65) and his wife Elizabeth (1707-66). George had been born the eldest son of an Eastbourne landowner. Elizabeth was the eldest daughter of John Collier, a lawyer whose connections included the Earl of Ashburnham and the influential Pelham family, and who was sometime Town Clerk of Hastings as well as the holder of many other important offices and agencies. George and Elizabeth had married in 1727 and lived in the town of Battle, six miles from Hastings. Like his father-in-law, George also practised the law and established himself with connections to other important local landowners. He was steward of the Battle Abbey estate from 1729 to 1757 and had dealings with the Whig politician Spencer Compton, Earl of Wilmington, who lived at Compton Place, Eastbourne.

One of the firebacks now resides at Great Dixter, at Northiam in Sussex, for which it was probably acquired by Nathaniel Lloyd when Edwin Lutyens was restoring and enlarging the house for him between 1910 and 1912. It is dated 1762, two years after the death of Elizabeth Worge’s father. He left her two thousand pounds in his will, a considerable sum in those days, which may well have been put to use in building the house at Starrs Green, Battle, which Samuel Grimm drew 20 years later. By then it was owned by Thomas Worge, George’s nephew. The house, on the south side of the road to Hastings, had been described by George as “my new erected Capital Messuage in Battle” in his will of 1765, which was drawn up (in exhaustive and repetitive detail – he was a solicitor after all) a fortnight before he died.

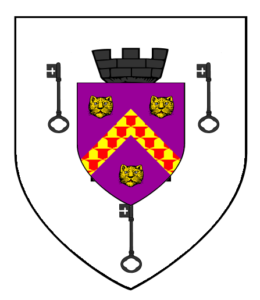

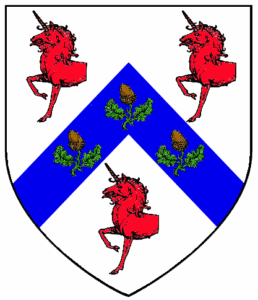

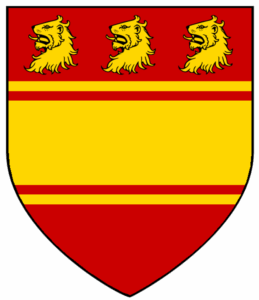

Central to the fireback is the shield of Worge impaling Collier surmounted by the Worge crest of a lion’s head erased (which, in heraldic parlance, means torn off). The shield is oval and unusual in that it is convex in relief. Some hatching to indicate the tinctures of the blazon has been included, which is uncommon on English firebacks, but it is incomplete. Burke’s General Armory describes the Worge arms slightly differently to the way they are depicted on both of the firebacks and on George’s marble ledger stone in Battle church. His arms are shown here as indicated on the fireback and on hiss memorial. The Collier arms are apparently the same as those of the Collyar family of Darlaston in Staffordshire, although how they are connected with the Sussex family is not known. Elizabeth Worge’s father was the son of an Eastbourne innkeeper, not someone to whom arms would normally be attributed.

The identical arms are on the second fireback, now in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. The rest of the back is utterly different. This time the same shield stands proud of a space in a baroque display of two beturbaned, naked men, a clam shell between them, and a backdrop of swirled foliage upon a low pedestal. The same Worge crest sits atop a lion’s mask. Several questions crave an answer: Was the convex shield specially made to decorate the firebacks, or did it come from another decorative feature in George and Elizabeth Worge’s home? The crest was clearly separate, so was it part of a larger armorial display? What prompted the design of this fireback, the carving of the pattern for which would have exercised a craftsman? Was the form copied from a design in a printed catalogue? Do both firebacks date from 1762?

Intriguingly, the second fireback is one of a pair, with the figures and their baroque setting common to both. However, on the other casting, instead of the Worge shield, there is the head of a man in profile, draped about the neck, within a wreath of laurel leaves, and instead of the crest there is what seems to be a flame. Presumably both were cast from a wooden pattern, so the potential is there for other castings to exist possibly with other decorative elements in the central space. Furthermore, the same wreath-encircled profile portrait is to be seen on a cast-iron panel, presumably originally one of a pair designed to flank a large fireplace, and implying a common source for the three castings. The exact form of the seated figure at the top and the flower design at the bottom is not clear.

If any readers of this note can offer suggestions that answer any of the questions posed above, I shall welcome them. My contact details are on the home page.