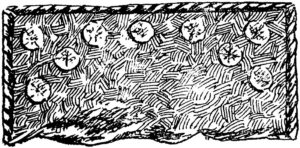

In my book, British Cast-Iron Firebacks, I described the series of backs that have been popularly associated with the battle against the Spanish Armada in 1588 because they bear that year embossed on the arch surmounting them and an anchor on one or more of their decorative panels. Their unique, modular use of individual carved pattern panels gave the founder some flexibility in his arrangement of them and of the width of the backs he cast. It had always been possible to extend the width and height of firebacks by the addition of plain or decorated extensions when copies were being cast, but probably the most commonly encountered version of the ‘Armada’ back includes the addition of a panel specifically, albeit rather inexpertly, decorated to appear to extend the elements of a particular combination of the original panels. That this was conceived later than the original panels is evident from the use of twisted rope, instead of the carved borders, for the edging, and what appear to be finger prints to simulate the soil surrounding the roots of the vines.

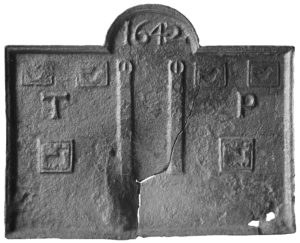

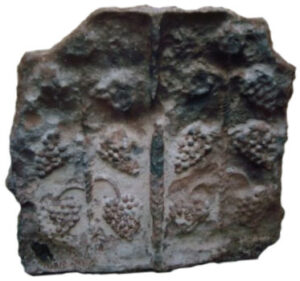

At whichever ironworks produced the original 1588 castings other firebacks were subsequently cast using this modular method but with other panels. This is uniquely demonstrated on a fragment of what must have originally been a significantly larger back. Only parts of two vertical panels have survived, one from the 1588 group and the other from ten years later. The incomplete, later panel shows an arrangement of plants, which can be more easily seen in a vase on a back recorded at Linchmere in Sussex on which is also a central panel showing a ‘knot’, popular in the late-Elizabethan period in the design of gardens. The arched panel on top with the date 1598 and the initials IM and IB, perhaps those of a couple at the time of their marriage, differs from the arched panel on the fragment which, although of the same date, has other initials (possibly I R) and repeated decoration. A fragment of another arched panel to the right hints at further vertical panels extending the fireback in that direction.

On the Linchmere back the arched panel is slightly askew, making it a different casting from the one used to produce the enlarged fireback in the Common Room at Goddards, a house at Abinger in Surrey designed in 1900 by Edwin Lutyens. Here, a 1598 casting has been copied at an early date to make a larger fireback with a recessed centre and with twisted rope decoration. The arched panel in this and other castings seen by the writer rests flat upon the vertical panels.

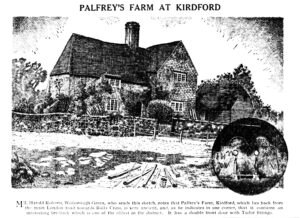

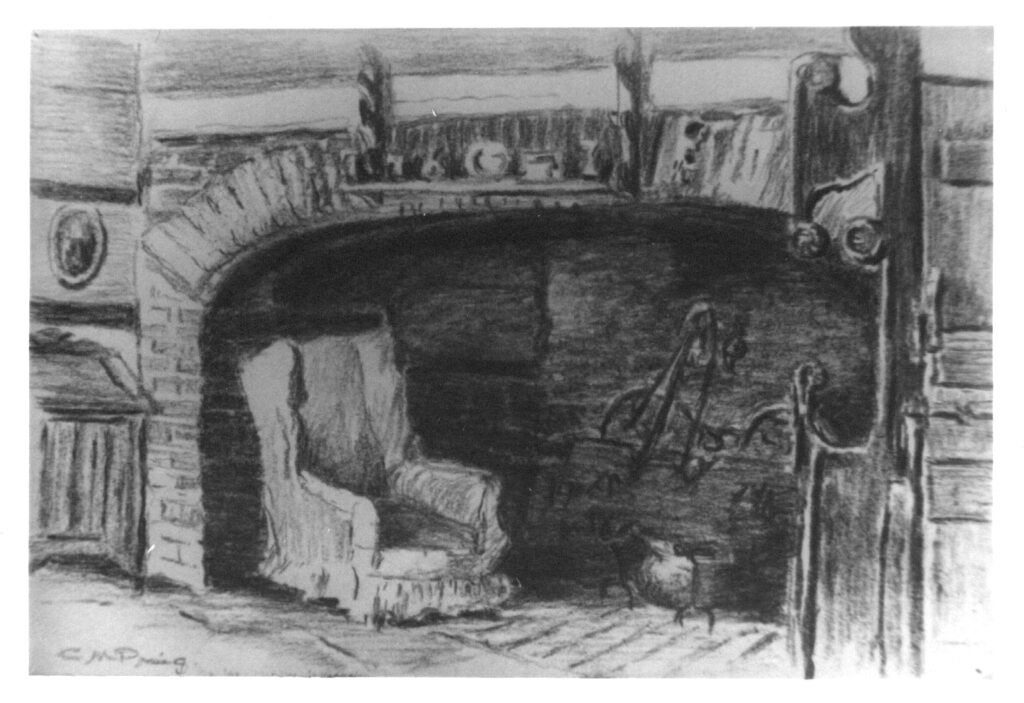

Returning to the 1588 group of castings, illustrations exist of a very different fireback which nevertheless is likely to have been a product of the same ironworks. A picture of Palfrey Farm, north of Petworth in Sussex, sketched by a Mr Harold Roberts, appeared in the West Sussex Gazette in February 1939. Roberts commented on the fireback he saw there and his drawing of it was included as an inset. Enlarged, it can just be made out that surmounting a somewhat unusually shaped quasi-rectangular back with initials and apotropaic rope designs are two of the arched panels from the ‘Armada’ series.

A further sketch, below, dating from 1942 shows the back still in position in one of the two original fireplaces in the house, but improvements to the property in the 1950s by the then owners, the Leconfield Estate, saw the fireback removed. Its present whereabouts, if it has indeed survived, are not known. Needless to say, if anyone reading this knows where it is, I should be most interested to learn of it (contact email on the Home page).

Although copies of the ‘Armada’ firebacks are now to be found all over the country and frequently appear in auctions and online marketplaces, the distribution of the rarer 1598 castings and the Palfrey Farm back suggest that the origin for the whole group may have been an iron furnace in the western part of the Weald of Sussex.

Finally, a separate note about the curious instance of an ‘Armada’ fireback with different initials that resides at Chawton House in Hampshire can be found at John Knight’s fireback.