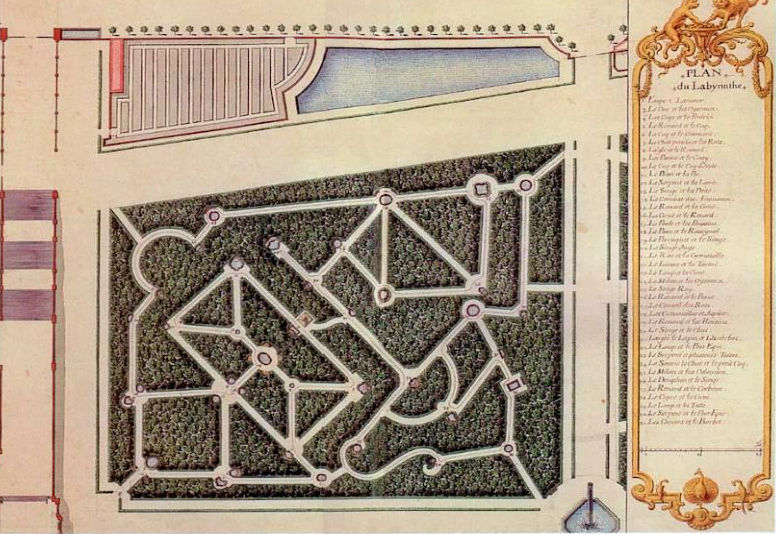

A garden comprising paths criss-crossing between trees and shrubs with fountains at the intersections of the paths had originally been conceived by the garden designer André le Nôtre, the artist Charles le Brun and the writer Charles Perrault for the chateau at Vaux-le-Vicomte, which had belonged to Nicolas Fouquet, one of Louis XIV’s principal ministers, but after his arrest, trial and imprisonment, the project was put in abeyance. At Perrault’s suggestion it was resurrected when Louis wanted something in the grounds of his palace at Versailles to educate and entertain his young son, also Louis, who was later known as the Grand Dauphin.

Designed by le Nôtre, who supervised its construction, the idea was that each fountain would illustrate a fable by Aesop or by Jean de la Fontaine and that a text in verse would be placed next to the fountain to provide a clue to the fable depicted. Building began in 1672 and took five years, many skilled craftsmen creating the 333 statues of animals for the 39 fountains. The Labyrinthe survived for less than a century, though, being replaced in 1775 by a garden in the English style for Marie Antoinette, the wife of Louis XVI.

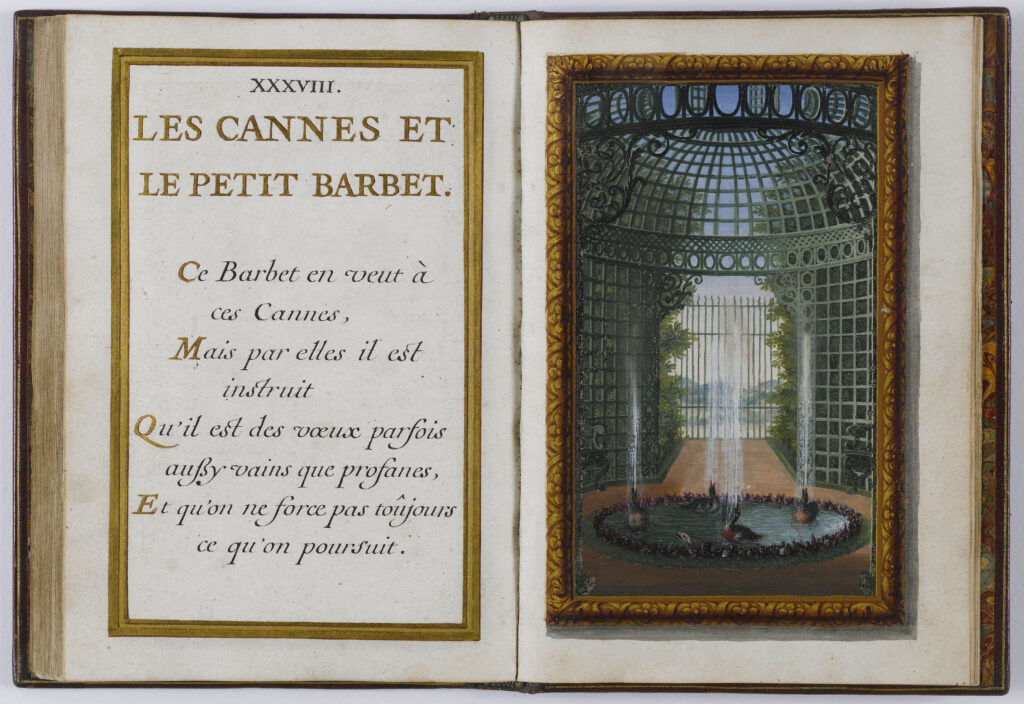

At the Labyrinthe’s completion, a book was compiled by Charles Perrault which included an engraving of each of the fountains by Sébastien le Clerc accompanied by an explanatory text by Perrault and the verses that had been written by the poet Isaac de Benserade. A special edition containing paintings of le Clerc’s pictures and of Benserade’s verses was prepared by Jacques Bailly.

The verse translates as : This barbet is after these ducks, but through them he has learned that some desires are sometimes as vain as they are profane, and that one does not always get what one wants.

So what has all this got to do with firebacks? The 38th fountain, though numbered 39 when an extra fountain was included, depicted a fable entitled ‘Les Cannes et le petit Barbet’ – The Ducks and the little Barbet. This is not one of the canon of Aesop’s fables nor is it one that was penned by Fontaine; in fact its authorship is not known. Perhaps it was written by Charles Perrault who was later to establish a reputation as the author of children’s stories such as Mother Goose, Cinderella and The Sleeping Beauty. The link with firebacks is that the pictorial scene on one of the castings first made in 1724 and bearing a pious inscription in Welsh was adapted from Sébastien le Clerc’s engraving of this fountain. The pattern-maker reduced the number of ducks with only one spouting the water and omitted the Barbet, but he included two birds flying over the fountain, which were copied from illustrations by the English wildlife painter and etcher Francis Barlow.

The pattern for this fireback is the subject of a watercolour in the collection at Hastings Museum, an inscription on the back indicating that the pattern had been at Mayfield in Sussex, although the fireback will not have been made there as none of the furnaces in that parish were still in operation as late as 1724. One cannot help but wonder if the pattern still survives in someone’s possession.