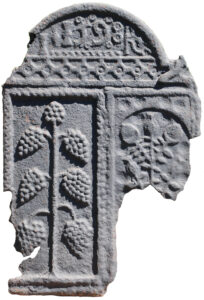

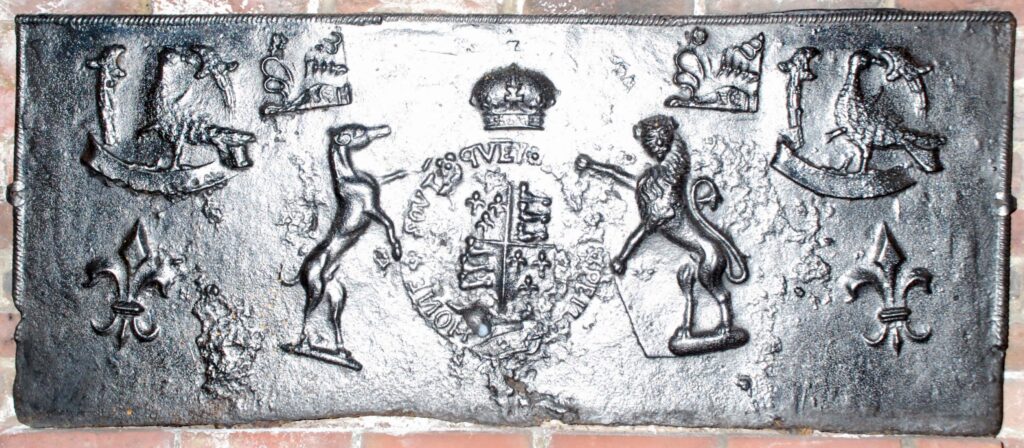

At least eight different, but distinctive, early firebacks all bear a Tudor royal shield, Garter and crown, as well as greyhound and lion supporters. The best example I have come across, in private ownership at Hatfield in Hertfordshire, is shown on the right. As shall become apparent, it is more elaborately decorated and better preserved than the rest. The Garter surrounding the shield has the mis-spelled motto: HONE SOVT QVEY MAL Y PENSE. The supporters appear to be free-standing figures, each with an attached, flat base. It also is decorated with arrangements of rope with fleur-de-lys terminals, which are a feature of a small number of late-Elizabethan firebacks.

What all of the other firebacks with this achievement of arms reveal is that each of these supporters was actually mounted on a backing board and, depending on how firmly they were over-pressed into the open sand mould, the shape of the backing can be seen. The flat base for each of the supporters was only intended to give the impression that they were free-standing when it was not actually so. The fireback at Alfriston Clergy House shows the arms with other decorative stamps, some of which have been noted several times on other firebacks and indicating that they had a common source. The particular style of fleur-de-lys is on two more of this group of armorial firebacks.

The shield and Garter formed one decorative stamp. This is evident on a uniquely shaped example, frequently copied in the twentieth century, where it had been inverted on the original casting. Such a mistake might have been easily made in the sixteenth century if the furnaceman responsible for arranging and impressing the various stamps into the sand mould was illiterate or, at least, unfamiliar with royal heraldry and the Garter’s Latin motto.

The combination of supporters is a guide to which sovereign’s reign the arms relate. The greyhound had originally been one of the supporters of the arms of Henry VII together with a dragon representing Wales, and also of Henry VIII in the early years of his reign. Although she most commonly used lion and dragon supporters, some heraldic authorities cite the use of the greyhound by Elizabeth I with a lion, so the arms displayed on this group of firebacks would appear to be from the reign of Elizabeth.

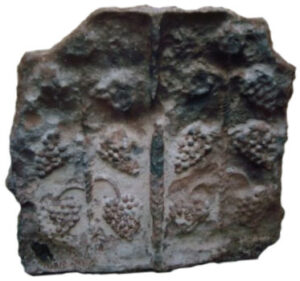

The addition of dates to firebacks normally indicates when they were cast. Two firebacks with these Elizabethan arms, each of a different size and proportions, carry a date of 1579 in a style untypical of the late-Tudor period. In both instances the armorials are very worn, suggesting long continuous use. The condition of the date in both instances, however, is relatively fresh, suggesting that the dates may have been added later.

A similar situation is suggested with two other firebacks both with a date of 1583. Again the firebacks to which the dates have been added are different in their size, edging and proportions and are well worn. The numbers are clearly shown mounted on a backing block and, this time, the style of the figures is more appropriate to the date they claim to be. If, as the supporters suggest, the four dated firebacks are from the reign of Elizabeth, which began in 1558, the corrosion affecting the armorials on each of them seems disproportionately advanced for use over what would have been a period of only 21 years in the case of the backs purporting to date from 1579, and 25 years for those dated 1583. It seems probable that, in all four instances, worn Tudor firebacks have been used to cast copies on which spurious dates have been included. They have then been subjected to further wear and corrosion through continued use.

The specific use of four different Elizabethan firebacks to attach false dates to is curious. Had the intention been to makes copies with fake dates one might have expected the same original fireback to have been used more than once. So the motive behind these castings is unclear, as is when they might have been cast. In the example from Groombridge Place (click on it to see it more clearly), the considerable damage wrought by long exposure to open fires suggests that these castings are not likely to have been made in the recent past.