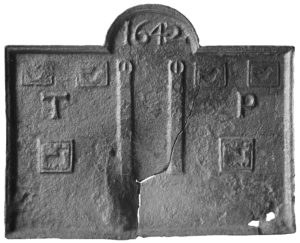

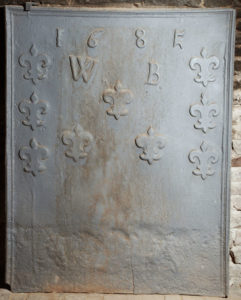

The pictorial decoration on late-17th and early-18th century British firebacks that aped the German backs made in the Siegerland for the Dutch market encompassed many themes. Most were allegorical scenes depicting the planets, continents or classical deities, all originally the work of continental artists. Half a dozen firebacks in the series made in 1724, which have designs of arrangements of flowers in various vases, may even have been inspired by similar decoration on oriental ceramics, then starting to be imported from China and Japan. Whoever carved the patterns for these castings drew upon an international range of illustrative sources.

One source, however, was of native origin. Francis Barlow (c.1626-1704) was born in Lincolnshire and trained as a painter and etcher of birds and animals, for which he became much appreciated. In his lifetime he became well-known for book illustration, and in particular of an edition of Æsop’s Fables published in 1666. Later he devised political cartoons satirising the Dutch, with whom Britain was at war in the 1670s, and the Popish Plot fraudulently alleged by Titus Oates. Many of his etchings were copied by other artists to form sets of engravings.

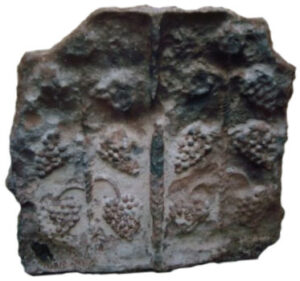

It is from engravings of Barlow’s etchings that the central elements of the two smallest firebacks in the series designed in 1724 were created. Both are of bird subjects, a peacock and a heron, and in both instances the depictions have been derived from engravings of Barlow’s work by the Bohemian artist Wenceslaus Hollar (1607-77), who lived and worked in England from 1637. Barlow’s study of a group of peacocks is undated but probably comes from the early part of his career. As in engravings of etchings generally, Hollar’s copy shows the scene in reverse. The pattern-maker has focused on the central bird for his design to the exclusion even of most of its tail feathers, the shape of the fireback precluding use of the landscape format of the original illustration. Sadly the only image of the fireback that is available is of a worn copy and some of the detail has suffered from the inevitable damage of regular exposure to fire.

The fireback showing the image of the heron, which comes from the same set of Barlow’s etchings as that of the peacock, has similarly concentrated on the main element of Hollar’s engraving, which like the peacock formed part of his Diversae avium species collection. The pattern-maker has even retained the hapless frog caught in the heron’s beak.

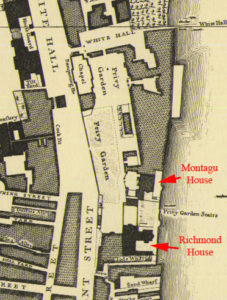

While carvers of patterns for firebacks in this period generally copied or adapted single illustrations for their subjects, and this included the two pictures by Barlow above, they also made use of details from his output as elements within their other designs. In Hollar’s engraving of the herons, one of them is shown flying. Barlow himself was not averse to reusing his own images of birds in several of his paintings and etchings; the same heron appears in the painting from Clandon House. The maker of the pattern for another fireback in the 1724 series has included the flying heron in a scene derived from a picture by Charles Perrault primarily depicting a fountain formerly in the grounds of the Palace of Versailles, as well as a flying duck that can also be seen on the Clandon painting.

That flying heron also appears on a fireback in the series identified by the monogram SHR in which a queen, possibly modelled on Queen Anne, but depicted as an allegory of the continent of Europe, is shown in a chariot being drawn across a parapet by a pair of horses. Allegorical figures in chariots representing the continents* originally appeared as a set of playing cards designed for Louis XIV by the Florentine artist Stefano della Bella, and the heron is also on another fireback in the series showing the figure of Africa. The identical bird reappears on a third fireback from the SHR workshop, this time flying above Venus with Cupid, as an allegory of the planet which bears her name. This fireback had been noted as early as 1699. The origin of its design was a set of engravings of the planets by Jan Sadeler from paintings by Marten de Vos dated 1585.

Two other birds on this fireback of the same period may also have been copied or inspired by Francis Barlow’s pictures. The central feature is a sea serpent fountain in imitation of a design by the French émigré artist Daniel Marot. This is another back in the series of 1724, the larger ones of which have a pious inscription in Welsh. The birds in this instance are a swan and a duck, both swimming in the water that surrounds the fountain. Given the incidental use of birds derived from Barlow’s etchings and paintings noted above it seems plausible that his output could have again been plundered here, although the poses of both birds are less idiosyncratic than those of the flying heron and duck.

Francis Barlow’s incidental images of flying birds provided a useful addition to pictorial designs on British firebacks and their use by pattern makers of stylistically similar work strongly suggests that either the firebacks were designed by the same individual or that more than one pattern maker was working collaboratively with colleagues over several years and having access to a common collection of visual resources from which they could derive the designs they carved.

*In the late-17th/early-18th century the continents were regarded as simply Europe, Asia, Africa and America.